Medieval Gesturing & Dog-heads

Part III on dog-headed men, exploration and secular writings, the human soul, and gesturing in the later Middle Ages.

How Human are dog-heads?

In some previous posts I've been zooming in on dog-headed men as a way to explore the human/animal boundary in medieval thought, art, and culture. To get into this post, here are the essentials:

Dog-headed men were among many "monstrous" peoples who were located on the edges of the map.

Medieval writers didn't care so much about whether or not they existed. There was "evidence" on both sides of that debate. The real question was: if I meet them, should I treat them as human or as animal?

To resolve that question, a few tests were cooked up over the Middle Ages. When we get to twelfth century and beyond—the time we care about right now—the test was basically:

There are three types of souls. Humans share a soul with angels and demons, this is an immortal and ‘rational’ soul. Animals have a different type, a ‘sensory’ soul which dies with them. The third type doesn't matter today.

How do we detect rationality from observation? We can't literally see the soul (nor should we kill other people to try):

One indicator was physiology—dog-men have dog's heads, and they ‘can't look up’ at Heaven—a sort of teleological ‘design argument’.

Another was behaviour—dog-men dress up in clothes and cover their private parts, which was ‘reasonable’ because it suggested they understood shame and virtue.

So was socialisation and society—if dog-men had ‘human’ (i.e., settled agricultural European-style) society, with houses and livestock and grain and meat, they were more likely human.

A great indicator was language and communication—and that is our focus today.

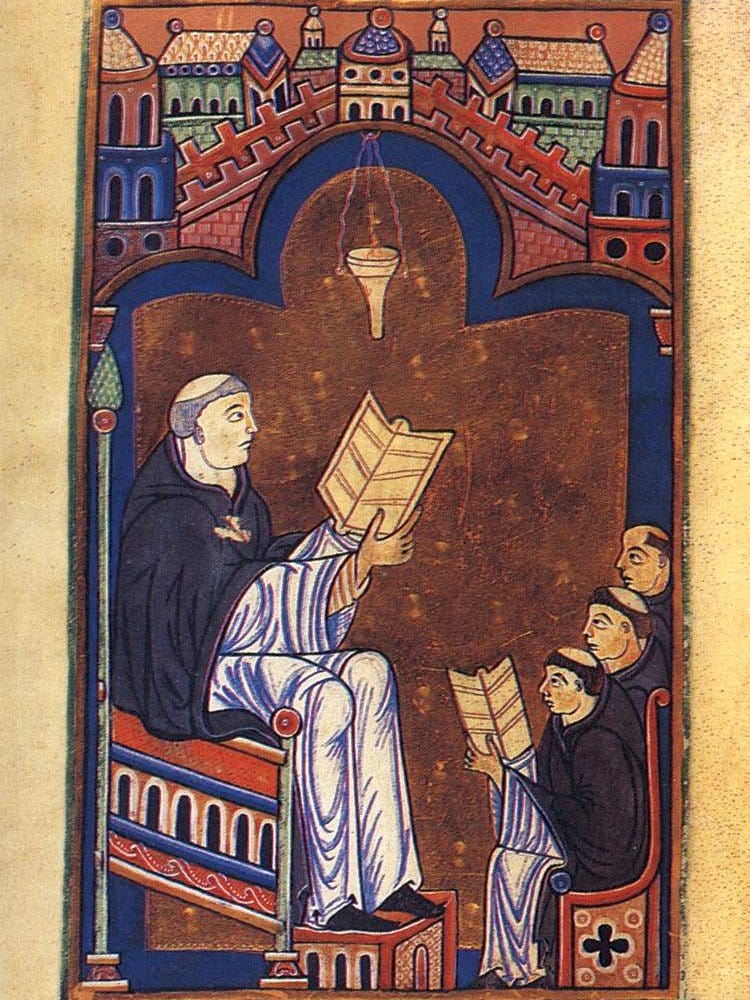

So, park that stuff about the soul and being reasonable and look back at this image (there are loads of examples, but I love this one):

These companion posts are not necessary but do check them out if you’re interested:

The problem with mythical dog-men

We know some friars went out into the ‘East’ and were laughed at by locals when they enquired about dog-men, and similar matters. Because we know now dog-men didn't exist, the stories were the primary source medieval people had. So was art.

But how do you show these indicators of humanity, like those listed above, in stories or in art?

I said language was important (especially in a society where not everyone is literate). Yet, language can also be a knock against our dog-heads. The idea some languages or communication systems were not rational is especially pertinent when we are talking about men with dog’s heads. They bark and snarl and whine. That’s what dogs do—not men. It is not rational. This seems to answer the question.

But what men and dogs both can do is communicate with their hands and bodies.

A microhistory of medieval gesture

Gesture is an immense and poorly-understood topic. We can gauge medieval gesture mostly adjacently, especially from courtesy and oration texts aimed at improving preaching and secular (i.e., legal) rhetoric. By the time of Hugh of Saint Victor (1096-1141), we start to see a distinction between gesture (gest) and gesticulation (gesticulatio).

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Livres des Merveilles: Cabinets of Curiosities to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.

![r/ArtefactPorn - Christ meeting the Cynocephali (dog-headed men) illustrated in the Kiev Psalter of 1397, known also as The Spiridon Psalter. [1436x1342] r/ArtefactPorn - Christ meeting the Cynocephali (dog-headed men) illustrated in the Kiev Psalter of 1397, known also as The Spiridon Psalter. [1436x1342]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!pui1!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fe242f66c-caf2-476a-93a0-2ab19f1b0222_640x598.jpeg)