The Goddess Natura

That's an evocative title. A medieval Christian goddess? Well, of sorts...

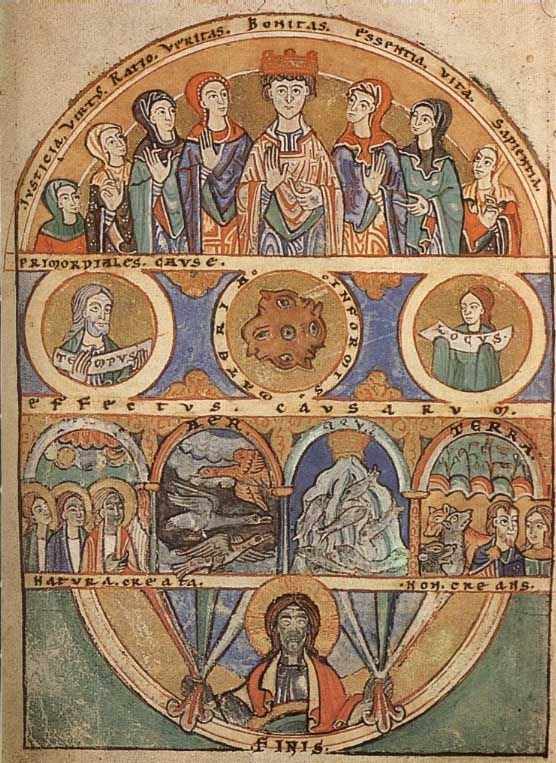

Conceiving creation

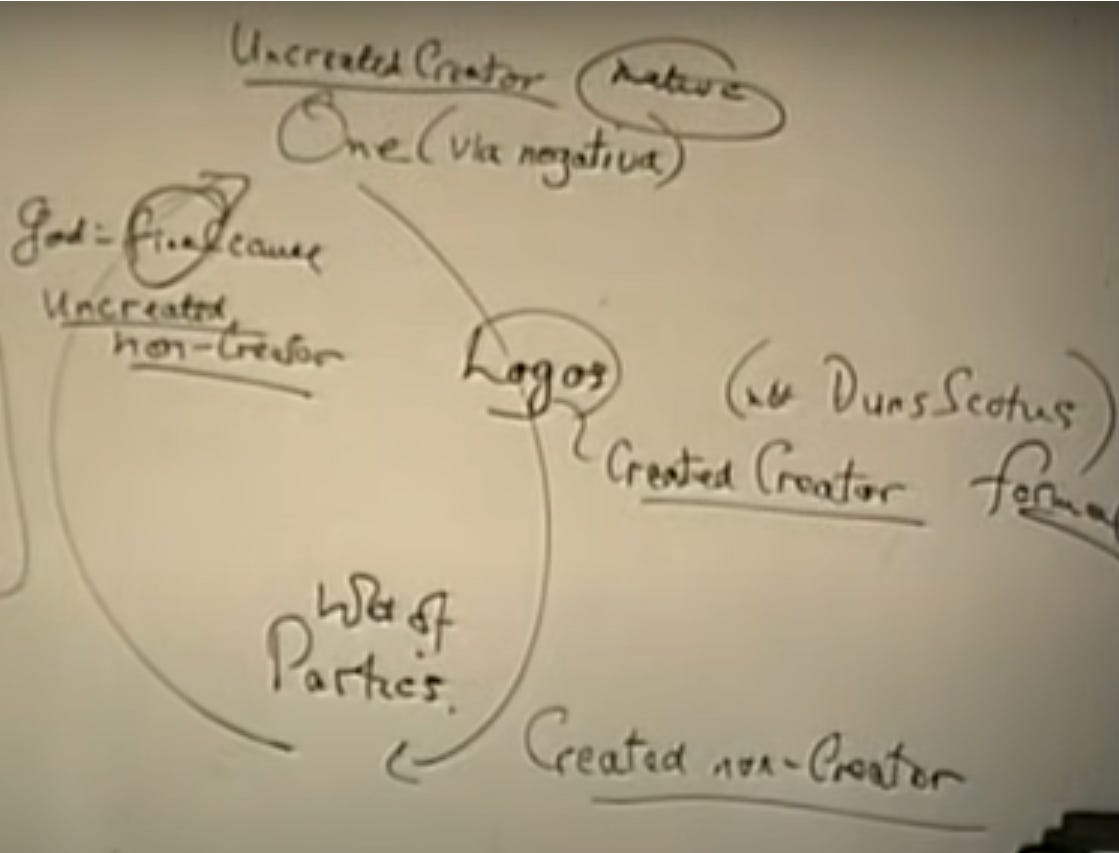

Let's talk medieval philosophy, specifically early medieval Neoplatonism. In Neoplatonic thought, which was popular in the court of Charlemagne and the Carolingian Franks (800 onwards), creation was conceived in a particular way. I'll let Dr Arthur F Holmes explain (I’ve cut to the pertinent diagram—don’t watch it all!):

This is the important part, the diagram he starts drawing after 10:26:

This is quite complicated especially in relation to forms, virtues, and ideas; but our dear John Scotus Eriugena (800-877) essentially categorised 4 Species of God/Nature that we can observe (though in absolute reality happen continuously together):

That which creates and is not created (God as the origin, creator ex nihilo);

That which is created and creates (i.e. Jesus, but also for us possibly Natura);

That which is created and does not create;

That which neither is created nor creates (God as the ultimate end/telos)

What does it mean?

So here we have a creator ex nihilo—God. But God can create his own creators, of course. Although omnipotent, omnipresent, etc., what if God created something to do the routine creating for him? The everyday blades of grass, the Spring lamb, and so on. Someone has to do that, you know. Or at least some medieval people thought so.

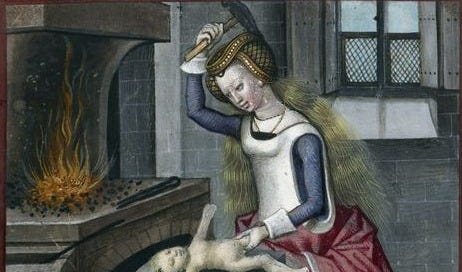

In comes Natura. Nature, the ‘goddess Natura’ does the routine fashioning of every organic thing—every baby born, every animal, every plant. Natura is a really exciting topic for a myriad of reasons. Reasons like these:

What happens if Natura makes a mistake? Unlike God, she is fallible. Only God is infallible, after all. Surely he would not allow cruelty, like birth defects, in his perfect creation.

What if Natura gets bored or wants to have a little fun? How about hiding some jokes in the world to trick curious people… or to make them reason about nature and so get closer to God.

Is Natura the only ‘goddess’? Are there multiple Naturae/s?

This might seem like a counterintuitive topic. I can hear your brain turning, wondering whether this isn't heresy. You aren’t the first to think so.

The initial answer is artistic license. Well, poetry, at first…

The Cosmographia

In 1147, a cleric called Bernadus Silvestris conceives of the creation of the universe in a somewhat unorthodox way. He turns the Biblical Genesis into a drama. Bernardus asks the question, what was happening behind the scenes of creation?

We begin with Megacosmus, which is about the creation of the universe, before we turn to Microcosmus, which is about the creation of man. Man and his world are intimately connected.

Our protagonist in this drama is Natura, who is tasked with fashioning stuff from a semi-sentient gloop called Hyle (God created the gloop called Hyle; Natura can’t create ex nihilo, remember? She also cannot destroy Hyle).1

Natura is an artificer, which will become important later. But she is also reluctant, and likes to complain, and is a bit annoying. This isn’t unreasonable—she has a big job.

Silva ‘an unyielding, formless chaos’ is supposed to hold Hyle in check—this primordial soup—but isn’t doing well:2

‘…Hyle exists in an ambiguous state, placed between good and evil, but since her evil tendency preponderates, she is more readily inclined to acquiesce to it. I recognise that this rough perversity cannot be made to disappear or completely transformed; for it is too abundant…’

Natura, has her disagreements with her mother Noys, ‘firstborn of God,’ who was ‘the knowledge and judgment of the divine will in the disposition of created things.’3 Noys proceeds to finally help Natura. Under Noys’ guidance, the four elements are drawn out of Hyle and the world soul, Endelechia, is born as a spouse for the world.

‘…I will refine away the greater part of the evil and grossness… I am fashioning a form for Silva.’

And Hyle became…

‘Nature’s most ancient manifestation, the inexhaustible womb of generation, the primal ground of bodily form, the matter of bodies, the foundation of substantive existence. From the beginning this capaciousness, confined by no boundaries or limits, unfolded such vast recesses and such scope for growth as the totality of creatures demanded.’

Silva’s beauty is restored and Noys is happy. But the universe is not done without man. Natura is sent out to find Urania and Physis. On the way, all manner of hijinx ensues. Natura bumps into Genius and collects the other two, they descend through the planetary spheres and meet Tugaton, the supreme divinity.

Finally, under Noys’ guidance, Natura, Urania, and Physis fashion man in such a way that human life will not pass away and the universe shall not return to chaos.

Wild.

And the best part? Cosmographia was read out to Pope Eugene III during Bernardus’ lifetime. Nothing happened—no cries of heresy or condemnation—in fact, Cosmographia would be one of the most popular manuscripts in Medieval Europe.

Natura after Bernardus

Certainly inspired by Plato’s Timaeus, Bernardus’ Natura as a character divorced from Platonism (and a few of his other characters) popped up throughout medieval texts.

Alan of Lille extended Natura’s complaining nature in The (Com)Plaint of Nature (c.1160) and helped to establish the character of Natura as theologically sound, being beneath God. Whilst Bernardus’ Natura complained about Creation, Alan had Natura complain about humanity, especially sex. Unsavoury moral objections aside, lots of sex means Natura is saddled with a lot of work fashioning babies.

Chaucer popped Natura into Parlement of Foules (c.1390s) and in Confessio Amantis (c.1390), John Gower (himself a Chaucer fan) included Natura among his short stories.

The most famous use of Natura is probably in the Romance of the Rose: a poem all about love, which had two parts (1230 and 1275). Rose was misogynistic and a risque text which had a massive circulation. Natura features throughout and as a result received many an interesting manuscript illumination.

After the Middle Ages

I don’t often venture post our Middle Ages… but when I first learnt about this, my next question was—well, what happened to all this? ‘Mother Nature’ seems like such a neopagan/non-Christian idea in our modern world, belonging to the New Age, ‘alternative people—like me’, as my mother would say.

I don’t have all the answers to this question (not yet) but I did write an essay once wrangling with it. There are some answers in the postmedieval, early modern world.

As art became increasingly important in Europe, Natura for a time went from Natura Artifex toward Natura Pictrix: she who paints her self. Historian Paula Findlen put it thusly:4

‘…age of natura pictrix expressed nature's ability to diversify; in this fashion she added color and shape to the world outlined by God…’

So far, so familiar. The idea is fundamentally the same—immense creative diversity, an awesome, limitless canvas, and power humans can only hope to emulate with their own art. What happened next (in this nutshell, reductive view of history)?

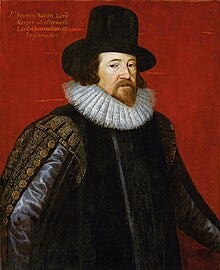

This guy, Francis Bacon, was a lawyer and politician and scholar probably best known for the ‘Baconian Method’ which helped articulate the language we still use when describing experimental science today.

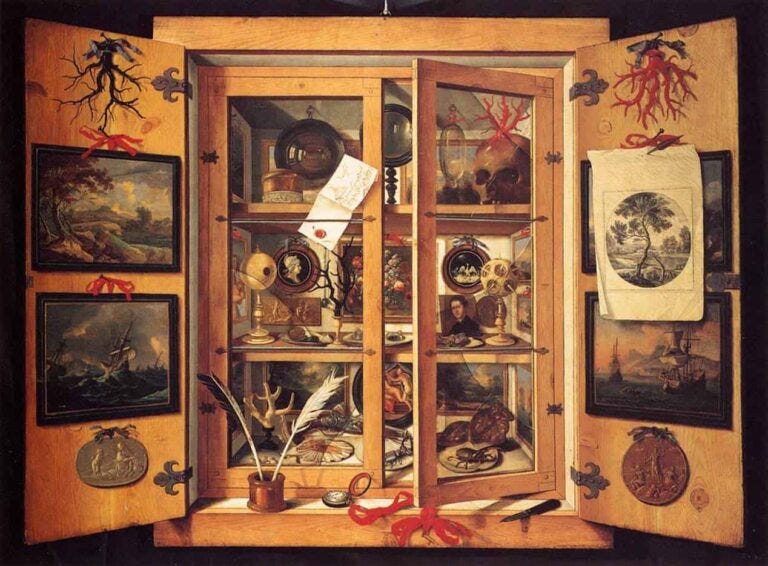

Bacon lived in a time when people loved collecting things and showing them off. Wunderkammer (Cabinets of Curiosities), and eventually musaea/museums, were all the rage. Collect, categorise, typify. I won’t go into too many details but this period brought marvels home.

People also used to start replicating marvels and wonders that they believed Natura had left behind as jokes (lusus—this will get its own post, just wait). The most significant of these man-made creations were things Natura apparently could not (or chose not to) make—automata. Clockwork was one thing, but using it to imitate and replicate the natural world was another. And yet, science was allowing people to do this. Humans were creating their own jokes. Jokes that could rival Natura.

Automata had been around for a long time—just look up the Antikythera Mechanism. Emperor Leo VI (r.886-912) installed ‘moving statues’ in Constantinople. So the leap into a ‘Scientific Revolution’ isn’t that simple but alongside this explosion in clockwork, great change had swept the theological and philosophical landscape of Christendom. The Reformation, for one. Now these semi-sanctioned ideas like a ‘goddess’ were less tasteful. But, if man can create a clock so perfect as to always tell the time, why can’t God? He obviously can.

So Bacon put it best when he said:

‘…History of Nature is of three sorts; of nature in course, of nature erring or varying, and of nature altered or wrought; that is, history of Creatures, history of Marvels, and history of Arts.’

And that’s just it. Suddenly Natura was not organic and playful and complaining. Genesis did not need a drama. Babies weren’t hammered into shape at the cosmic forge. Nature was a perfect mechanism. She was clockwork, designed perfectly by God and set into motion.

If His mechanical universe was already perfect and the science agreed… What was the point of God if He’d done all the creating already?

Well, that’s a story for another day.

If you’re interested in this topic, see Barbara Newman’s 2003 monograph God and the Goddesses: Vision, Poetry, and Belief in the Middle Ages. She was my main source whilst studying and goes into much more precise detail than I, with compelling analysis from chapter 1 and throughout. Chapters 2 and 3 are dedicated to Natura and her evolution. Thank you to Christina Van Dyke in the comments for reminding me!

Besides Newman, see also:

Otherwise, thank you for reading! If you liked this post, check out:

I post at least once a week.

Subscribe to join me on this journey through medieval marvels and mysteries. Question:

What part of our whistle-stop tour of Silvestris’ Cosmographia was most interesting to you? Which character would you like to learn more about?

Drop your thoughts below—I’d love to hear them, and any ideas for future posts you’d like to see.

Hyle means forest in Greek (as Silva means it in Latin) but it is also what Aristotle called the primordial matter (soup?) from which the world was formed.

Often interpreted as Providence or Divine Will.

This is taken from the 1973 translation Megacosmos by W Wetherbee, particularly pages 13-17.

Taken from her fantastic article ‘Jokes of Nature and Jokes of Knowledge: The Playfulness of Scientific Discourse in Early Modern Europe.’

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Livres des Merveilles: Cabinets of Curiosities to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.