Introducing the Medieval Marvel

A bumper-length introductory post: take it at your own pace

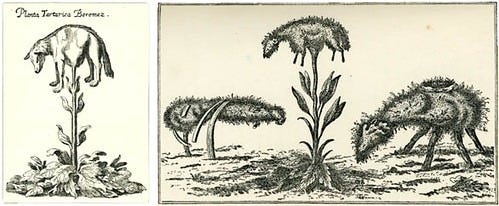

‘…A man who goes from Cathay [China] towards India the Greater and the Lesser will go through a kingdom called Cadhilhe [Kao-li, possibly Korea], which is a great land. There grows a kind of fruit as big as gourds, and when it is ripe men open it and find inside an animal of flesh and blood and bone, like a little lamb without wool. And the people of that land eat the animal, and the fruit too. It is a great marvel. Nevertheless I said to them that it did not seem a very great marvel to me, for in my country, I said, there were trees which bore a fruit that became birds that could fly; men call them bernakes [barnacle geese], and there is good meat on them. Those that fall in the water live and fly away, and those that fall on dry land die. And when I told them this, they marvelled greatly at it…’

What you have just read is taken from English author John Mandeville’s Travels (c.1357-71), chapter 29: Of the countries and isles which are beyond the land of Cathay [China]; and of different fruits there; of the twenty-two kings shut in within the mountains, from Moseley’s excellent translation and commentary.

What the hell is Mandeville talking about?

Besides being a fascinating source for the medieval European view of the world (which will get its own post), Mandeville is specifically recounting two very famous marvels. The first marvel is the vegetable lamb. Going back to the ancient world, this marvel was associated with two places in the ‘East’: Scythia and Tartary.

A popular theory about the vegetable lamb is that it originally described cotton.

The second is the marvel of barnacle geese. Cleric Gerald of Wales (1146-1223), surveying Ireland to help justify English invasion in Topographia Hibernica (1187), wrote:

‘…there are many birds called barnacles (bernacae)…nature produces them in a marvellous way for they are born at first in gum-like form from fir-wood adrift in the sea. Then they cling by their beaks like sea-wood, sticking to wood, enclosed in a shell-fish shells for freer development…hence in some parts of Ireland bishops and men of religion make no scruple of eating these birds on fasting days as not being flesh because they are not born of flesh.’

Meanwhile, ornithologist, linguist, and Holy Roman Emperor Frederick II (1194-1250, nicknamed Stupor Mundi—Wonder of the World) expressed some serious scepticism about the existence of barnacle geese in his De Arte Venandi cum Avibus, Book 1 C. Ch.XXIII-F ‘On the Nesting of Birds’:

There is also a small species known as the barnacle goose arrayed in motley plumage…There is however a curious popular tradition that they spring from dead trees. It is said that in the far north old ships are found in whose rotting hulls a worm is born that develops into the barnacle goose. This goose hangs from dead wood by its beak until it is old and strong enough to fly.

We have made prolonged research into the origin and truth of this legend and even sent special envoys to the north with order to bring back specimens of these mythical timbers for our inspection. When we examined them we did observe shell-like formations clinging to the rotten wood, but these bore no resemblance to any avian body. We therefore doubt the truth of this legend in the absence of corroborative evidence. In our opinion this superstition arose from the fact that barnacle geese breed in such remote latitudes that men in ignorance of their real nesting places invented this explanation

Marvels, Miracles, and understanding the World

Marvels are an expansive subject and I think quite a fun one. There are so many ways one can take them—from ‘jokes of nature’ to dog-headed men to seas made of gravel. They are found everywhere, but especially on the periphery and the edges of the familiar. They help us understand the rich way medieval Europeans understood the world and their place in it. They reveal the importance of curiosity and wonder and its influence on philosophical, theological, and scientific inquiry. Medieval minds knew marvels were distinct and worthy of note. They revealed God and Nature’s immense creative power and boundless diversity.

But marvels also had a specific place. These were not miracles—rather, defining them against miracles is one way to understand them. Miracles were acts sanctioned by God that upturned the natural order and temporarily altered the laws of nature. Only God could perform miracles, and those who he performed miracles through were saints—another story for another post.

But if marvels are notable for being atypical, how is that different? Well, marvels were not one and done events. Marvels were there, in nature (or in accounts of nature) that could often be sought out, seen, wondered upon, sometimes collected or recorded, and studied—and indeed they were. If a marvel was purely folkloric or part of an untrue mythical tradition, what did that reveal about a person or their culture?

The Purpose of Marvels

For some, like Marsilio Ficino (1433-99), wonder was a philosophical obligation. For others, like Aquinas’ teacher the great cleric and natural philosopher Albertus Magnus (d.1280), marvels were part of a broader endeavour of cataloguing and properly understanding the natural world. For travel writers like Ibn Battuta (1304-69), John Mandeville, and Marco Polo (1254-1324), marvels were par for the course—as Mosely put it, for a travelogue to be taken seriously, marvels were a must. For travellers with missionary, political, and philosophical concerns, like William of Rubruck (fl.1240s/50s) or Ordoric of Pordenone (1280-1331), discussing marvels and their existence or lack thereof with locals was an important part of their journey. Marvels figured throughout narratives, like the famous Alexander (the Great) Romances, the Matter of Britain, and werewolf stories. And for those like our Holy Roman Emperor the Wonder of the World, marvels were a complex matter which evidence might prove was mere superstition.

Saints such as Mercurios feature marvellous peoples in their tales. In the Orthodox world, Saint Christopher himself was depicted as a cynocephalus, or dog-head, owing to his travelling and marvellous nature—though mostly in postmedieval art.1

Marvels are Fun

Where does that put us? Medieval audiences did intellectualise marvels, but in my view there is just a fantastic curiosity to them which is very human. Marvels were popular because they were interesting. They spark the imagination.

For fiction writers, especially fantasy and historical fiction, I find marvels are just about the most interesting real-life example of successful, collaborative worldbuilding. There is so much rich inspiration to draw from marvels themselves, but also the way marvels and news about them was transmitted, disputed, collected, and studied. The most obvious example of such inspiration done very well is Umberto Eco’s Baudolino (2000) which is an all-time favourite novel.

And because I find them fun, I’m just going to list a series of marvels—many of which feature in Mandeville’s Travels, though far from exclusively.

1. The Monstrous Races or Species

Among the most interesting marvels are nonhuman-peoples, commonly grouped together as ‘monstrous races’. Unlike unique, prodigious monsters—people born with specific characteristics or qualities that tells both of Natura’s creative power but also ominous signs from God (which will get its own post)—the monstrous races are a discrete set of people, often thought about in clusters, kingdoms, or tribes. Many, if not all of the monstrous races were inherited from the classical and ancient world. Writers like Pliny the Elder, Herodotus, and Solinus, included them.

The most interesting are the dog-heads who will get a dedicated post. Others include:

the blemmyae (men with their faces on their torsos, often lacking heads);

the sciapods (men with one foot which they use to run very fast and shade themselves from the baking sun of the ‘Indias’);

the panotti (men with long, floppy ears);

the hippopodes (men with horse’s hooves);

…and so many others—from cyclopes to pandae to oönæ to astami to donestre to pygmies. As Robert Bartlett put it in his Natural and Supernatural in the Middle Ages, these were people who always lived on the periphery. For a traveller going to that periphery—whether Ratramnus in the Arctic, Marco Polo in Asia, or Sir Francis Drake in the Americas—the monstrous peoples were expected to be there.

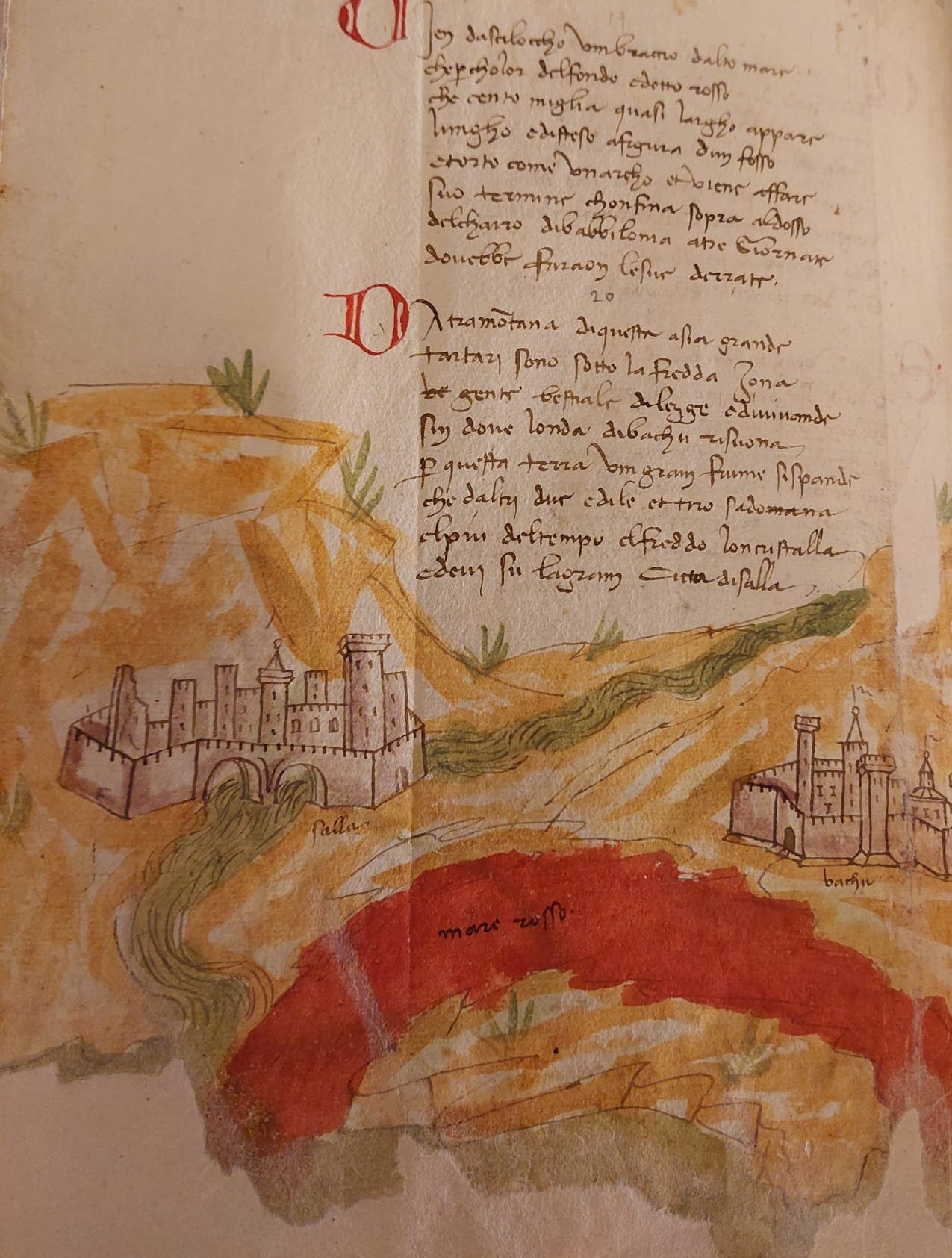

2. The Gravel Sea and Prester John

Prester John, a mythical Christian king Crusaders thought would come to their aid in the Holy Land, is a marvel unto himself and deserves his own post. His mythical kingdom in central Asia (‘the Indias’) was often described full of unique wonders and marvels, both geographical features and animals. John Mandeville describes crossing the ‘Gravelly Sea’ like this:

‘…And he hath under him seventy-two provinces, and in every province is a king. And these kings have kings under them, and all be tributaries to Prester John. And he hath in his lordships many great marvels.

For in his country is the sea that men clepe the Gravelly Sea, that is all gravel and sand, without any drop of water and it ebbeth and floweth in great waves as other seas do and it is never still ne in peace, in no manner season. And no man may pass that sea by navy, ne by no manner of craft, and therefore may no man know what land is beyond that sea. And albeit that it have no water, yet men find therein and on the banks full good fish of other manner of kind and shape, than men find in any other sea and they be of right good taste and delicious to man's meat.

And a three journeys long from that sea be great mountains, out of the which goeth out a great flood that cometh out of Paradise. And it is full of precious stones without any drop of water, and it runneth through the desert on that one side, so that it maketh the sea gravelly; and it beareth into that sea, and there it endeth. And that flome runneth, also, three days in the week and bringeth with him great stones and the rocks also therewith, and that great plenty. And anon, as they be entered into the Gravelly Sea, they be seen no more, but lost for evermore.

And in those three days that that river runneth, no man dare enter into it; but in the other days men dare enter well enough…’

Moseley believes this is the Taklamakan Desert. Seas are quite interesting as marvels, for the Dead Sea often conjured interesting accounts, as did maps depicting the Red Sea as—literally—a red sea:

3. Rhinoceros and Unicorns

‘…There are also other kinds of animals, as big as horses; they are called louherans, and some call them touez, and others odenthos [the rhinoceros]. They have black heads and three horns on the brow, as sharp as swords; their bodies are yellow. They are marvellously cruel beasts, and will chase and kill the elephant…’

Animal marvels are interesting because of the way these stories, especially in bestiaries, represented religious stories. Related to these theological dimensions, secular elites adopted the symbols of animals (real and mythical) in their heraldry, to identify not merely with the animal as we nowadays know it, but also the marvels they were associated with.

The classic example is the Scottish unicorn—typically, unicorns were thought to be the enemy of the lion, who would always come out victorious when they did battle. Who used the lion? The English.

Narwhals

Unicorns are a rich marvel unto themselves. Another angle which makes them interesting is the economy associated with marvels. Not unlike miracles being associated with votive offerings and especially relics, objects associated with certain marvellous creatures and plants had economic value. In Greenland, narwhal horn was a frequently traded commodity and masqueraded as having come from a unicorn. Indeed, before the complex events that led to its demise, Greenland relied on demand from marvellous and rare animal products, from seal skins, ivory, and gyrfalcons to the much-prized ‘unicorn horn’.

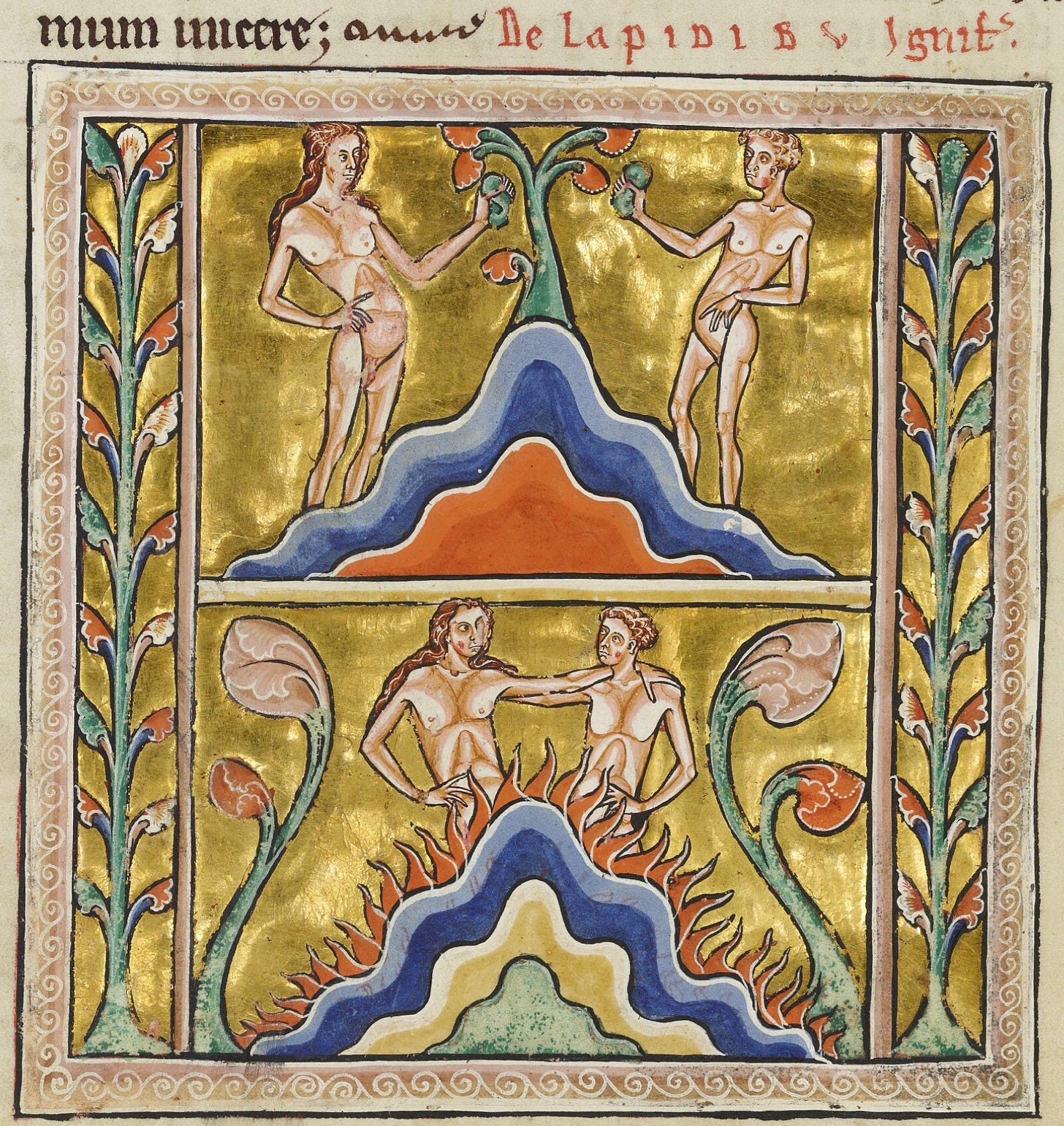

4. Firestones

The bestiary of Guillaume le Clerc (George C. Druce translation (1936)) states:

In the East there far above / Are two stones on a high mountain / Which have a very strange nature, / For they bear fire and heat, / They are as male and female. / Did you ever hear a story / More wonderful or more true, / For the books make us believe it? / When these stones are far apart, / Fire does not issue for any purpose / But when by chance it happens, / That the one comes near the other, / They kindle and fire comes out / Which burns up both the stones, / And so greatly the fire waxes and grows / That it kindles all the mountain / And whatever there is on each side / Of the mountain kindles and burns

Marvellous stones had many applications, often with magical associations. From Icelandic ‘sunstones’ to locate the sun lost in an overcast sky, to magnetic lodestones, and their applications for navigation and relationship with basilisks, we will investigate marvellous geology in future posts.

5. Fossils?

Fossils—fish imprints on mountain peaks, dinosaurs buried like dragon bones? Those were a type of marvel that would later be called ‘jokes of nature’ (lusus naturae) and they would become very important, enough to merit a post of their own…

We’ll leave it there, for now. As Mandeville said, with his usual wry wit:

‘…there are many marvels which I have not spoken of, for it would be too long to tell of them all. And also I do not want to say any more of marvels that are there, so that other men who go there can find new things to speak of which I have not mentioned…’

If you liked this post and want a follow-up on Mandeville, please do read Charles Moseley’s brilliant article on the Travels, with literary analysis, marvels, and some reflections on the author’s identity and his many afterlives. If nothing else, it’s great advocacy for why you ought to read the whole travelogue!

What’s Coming: Magic and Marvels Ahead

On this blog we’ll explore the rich, strange, and wondrous world of medieval magic but also the equally rich, strange, and wonderful world of medieval marvels.

We will do this through discussions like:

And in future posts:

Jokes of Nature: What do the vegetable lamb, fossils, and smiling clouds have in common, and how did they eventually help to break time as Europe knew it?

Necromancy—Fantasy and History: From reverse exorcism to armies of skeletons, what was necromancy really?

We’ll dive into forgotten texts, meet some people who practiced magic, and explore the marvels that defined medieval thought.

I will aim to start with one post a week, every Monday morning.

This has been a special bumper post, extra-long, but not meant to be necessarily absorbed in one go. Future posts will be much shorter and more manageable.

Final Thought: A World of Wonder

Marvels were rich and provide a fantastic vehicle to understand the history of ideas, travel, philosophy, and culture. They are at times problematic, at others baffling, and always a source for curiosity and interest. What makes this blog important is the attempt to try and capture, and through each fascinating marvel try and understand the medieval world. As a companion to medieval magic, marvels become increasingly rich and increasingly striking.

It’s time to uncover that world.

Subscribe to join me on this journey through medieval marvels and mysteries. Question:

Scholars have proposed an idea that modernity means ‘disenchantment’ with the world. What do you think? Have we lost the idea of wonder and marvels in the modern age? Is that what modernity means?

Drop your thoughts below—I’d love to hear them, and any ideas for future posts you’d like to see.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Livres des Merveilles: Cabinets of Curiosities to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.