A Promise to the World

In my last mini-curio, I referenced the fact that I haven’t actually gone over the medieval universe. I promised to do so, but it’s a huge ask, so this is post will serve as a touch-stone.

Also, I don’t discuss how the universe was thought to have come into creation here—Genesis does a lot of heavy lifting, but for more on that, check this out:

Cosmologies

There are, as I see it, three things baked into the word “cosmology”—literally study of the world. Let’s call these “scales”:

There is the universe in the broadest sense. I’ll call this scale 1.

Then, there’s the world in an Earthly sense—scale 2.

Finally, there is also local cosmology—micro-maps, meaning man, his organs, but also the local area, and so on. A more dynamic, localised sense of “world”: scale 3.

I like this three-part model because it is quite medieval in outlook—that is to say, the three are intimately linked in the medieval worldview. For Livres des Merveilles, this manifests most clearly when I write about astrology and astrological magic, which were fundamentally about the sympathetic relationships between these senses of cosmology.

The second and equally important part behind cosmology is meaning. Medieval cosmologies, in all the three senses, had spatial and religious//moral and geographical//cultural and Biblical imperatives. These were not just dual meanings—they were concepts that were fundamentally attached to one another, and meant to be understood that way. It all goes back to the recurring theme about belief.

So, with that said, I want to set up the most orthodox medieval cosmology (focusing on scale 1) before introducing three “idiosyncratic” models, just to demonstrate diversity in cosmological thinking.

The three idiosyncratic models were conceived by Cosmas Indicopleustes (sixth century), Hildegard of Bingen (1098-1179—referenced here!), and Nicole Oresme (1325-82). We have a late antique Egyptian merchant and travel writer; a High Middle Ages German polymath abbess; and a later medieval French university scholar and counsellor. How exciting!

But first, Aristotle & Ptolemy

Until Copernicus’ push for a heliocentric (sun-middled) universe, the prevailing model was anthropocentric (human-middled). It was anthropocentric for two reasons: the Bible and Aristotle. For shorthand, this combo will be called “scholastic”. The scholastic model wasn’t just anthropocentric—it was also finite, immutable, and ordered in a perfect, concentric (onion-like) way.

We can credit this shape to Aristotle’s Physics and Ptolemy’s astronomy.

Basically, Earth is in the middle and is static—it does not move. The planets (and some stars) are really “spheres” with lights in them, stacked on one another, and these turn independently

Biblical space

One thing the Bible doesn’t really define is cosmology. We have a vague idea (Firmament, Heaven, Hell, for example) but even the world-scaled cosmos is pretty undefined. All you know is there is an Earthly Paradise and a Holy Land, with some notable settlements. There are some international environmental events, like Noah’s Flood, but mostly it is localised to a small area where key events take place.

Meanwhile, Aristotle had a pretty coherent model for the universe in his Physics which was visualised thanks to Ptolemy. His work had been gobbled up by Arabic intellectuals, who adapted his ideas to a monotheistic, divine-empowered, Abrahamic universe.

In the twelfth-century, odd, Aristotle and his Arabic commentators were translated (mostly in Spain, mostly in Toledo) into Latin. This was a huge shift across the spectrum, but for our purposes it helped to crystallise the scholastic model which would persist through Copernicus and onwards. We call this model the “orthodox” medieval universe.

Biblical space-time

As an aside, I believe the Bible’s nonchalant approach to cosmology gave it appeal both to laypeople (by focusing on human drama) and to scientists (who knew there was stuff to be known—how did God create Earth, why, and what does it look like—but also relative freedom to find out). It also gave the Bible wiggle room and compatibility with various cosmological ideas and models. That the scholastic model was orthodox is by-the-by, because proper learning—the fundamental purpose driving all this—meant the Bible allowed for a Copernican and later cosmologies which were not human-centric, were not limited, were not concentric, and were, eventually, not even operated on divine principles, but mechanistic ones.

Contrast this loose and flexible approach to space in the Bible with time. The Bible, crucially, rested on providing an authentic, spiritual-historical account. But, it was fundamentally incompatible with natural history (geology, palaeontology) and human history (archaeology especially). Fossils show this logic very clearly, and how it ultimately led to disillusion with the Bible as an authoritative text compatible with mainstream science. In short, scientific inquiry had shown the Bible lacked a useful cosmology—but at least it was flexible to incorporate most models. However, scientific inquiry then shewed that the Bible had a rigid and incompatible theory of history. No wonder that both revolutions and theories of history (professional, Hegelian, Marxist) accelerate in this time (the nineteenth century)!

Orthodox cosmos

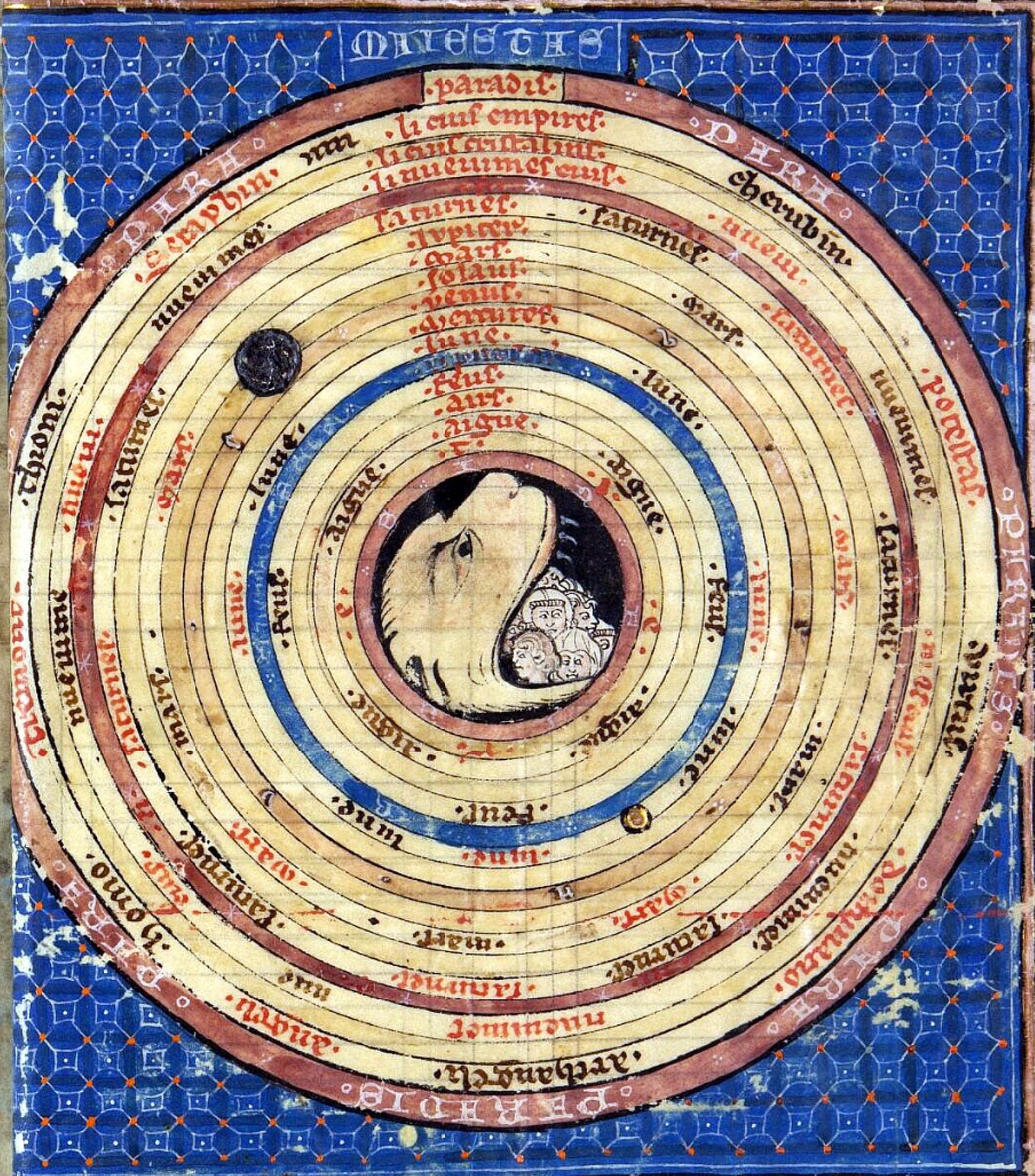

The scholastic model is very satisfying. Earth is in the universe’s centre, and inside Earth’s centre is Hell (hence Dante). Beyond Earth’s firmament are the sublunar spheres, which move in regular shells around Earth, composed from basic elements. Beyond the Moon are the superlunar spheres, composed from aether (the fifth element), and eventually the Heavens.

Beyond the Heavens? Either nothing, or infinity—it doesn’t matter. Dante and many others also subdivided the Heavenly spheres, right up through the crystalline heaven and into the empyrean. We’ll come back to this!

In a way the model is also one which rates chaos (Hell, Earth, sublunar spheres) up to increasing stasis (eventually the perfect, ordered stillness in the heavens). Everything sublunar is subject to sympathetic elemental relationships—most among all, humanity, who are fundamentally the centre.

Scale 2 in orthodoxy

We’ve looked at the orthodox scholastic model, which accounts mostly for scales 1 and 3. But what about scale 2, namely the cosmology on Earth? Well, here is where the Bible is a bit more authoritative and the Greco-Roman influence a bit less subtle than just finger-pointing at Aristotle.

I covered this in a lot more detail here:

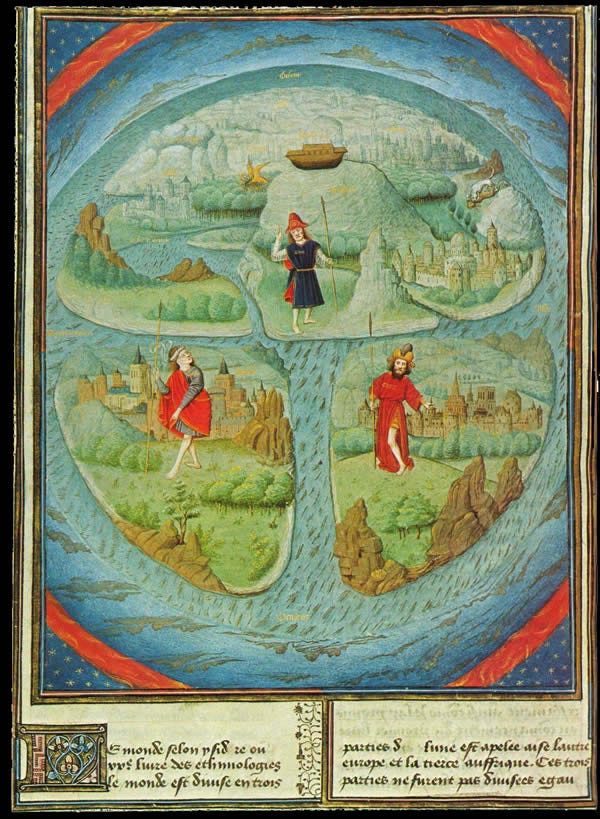

But the basics are that maps were “easted” (the top points east, not north). The centre was always the Holy Land. The Earthly Paradise usually appears as the source for the major rivers which were thought to divide the three continents: Africa, Europe, and Asia. This is all very Greek, by the way. Some maps also include an antipode—another Greek-originating theory, that there is an equal and opposite continent on Earth’s other cheek, to keep everything in balance.

These maps came in three broad flavours: (1) “T and O” maps, (2) anthropomorphised maps, and (3) “realistic” (sailing) maps. The first type describes the look: a “T” shape (the divided continents look like a T) surrounded by an “O” or a ring, encircling the sphere (like a coin, where the other side would have an antipodal continent). The second type can look very strange to us moderns—the same basic premise, but mapped onto a person, usually Jesus Christ. Flavour (2) maps are intentionally making a moral point about the world’s coherence and necessity of but also types of countries and peoples located at points in the body. Flavour (3) is the most intuitive, because it is basically the precursor to what we think when we talk about maps today. The three flavours do blend into one another. As discovery and the new continents popped up, the most useful maps were those that showed a more accurate and reliable way to travel, and so flavour (3) led the way.

Back to universes now.

Cosmas Indicopleustes

So, about seven-hundred years before our orthodox, scholastic model, we turn to a merchant-traveller-cum-hermit called Cosmas. Very on-brand first name, and his second name (meaning ‘came from (the) India(s)’) is also very on-brand.

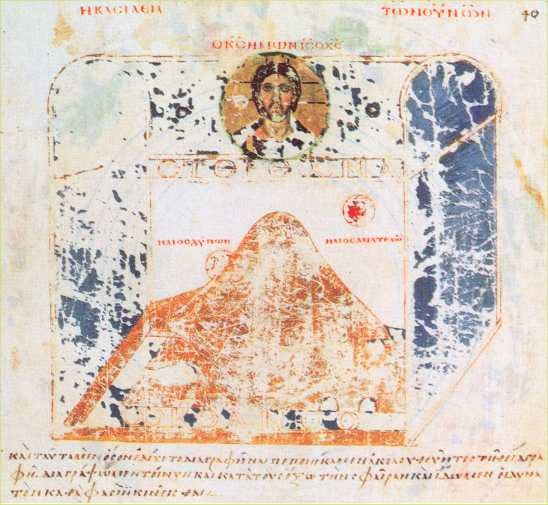

Cosmas was very well travelled (we think, or so he says). Back in his day, though, all the above stuff was a bit less directed. Let’s cut to the chase—Cosmas thought the universe was shaped like a tabernacle or Ark of the Covenant. Within the universe was a parallelogram-shaped Earth enclosed by four oceans.

What does that look like? Like this:

Cosmas lived in an age where Christianisation had come into its own and established itself in the Roman Empire. It was now trying to reckon with itself and consolidate organisation, power, and orthodox theology—by dealing with heresy after heresy.

From that perspective in late antiquity, and the rich symbolic repertoire in Eastern Roman devotional art, Cosmas’ tabernacle is quite a clear and powerful symbol for the shape of the world. It was not, however, a valuable one for practical means. Nor can we say with much confidence Cosmas’ work was disseminated.

Hildegard of Bingen

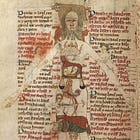

Hildegard is probably the most influential thinker mentioned in this post, Aristotle and Ptolemy excluded. She was an illiterate abbess who composed music, devised medical herbals, led a convent, and had some seriously intense visions. She had a pretty badass nickname: Sibyl of the Rhine.

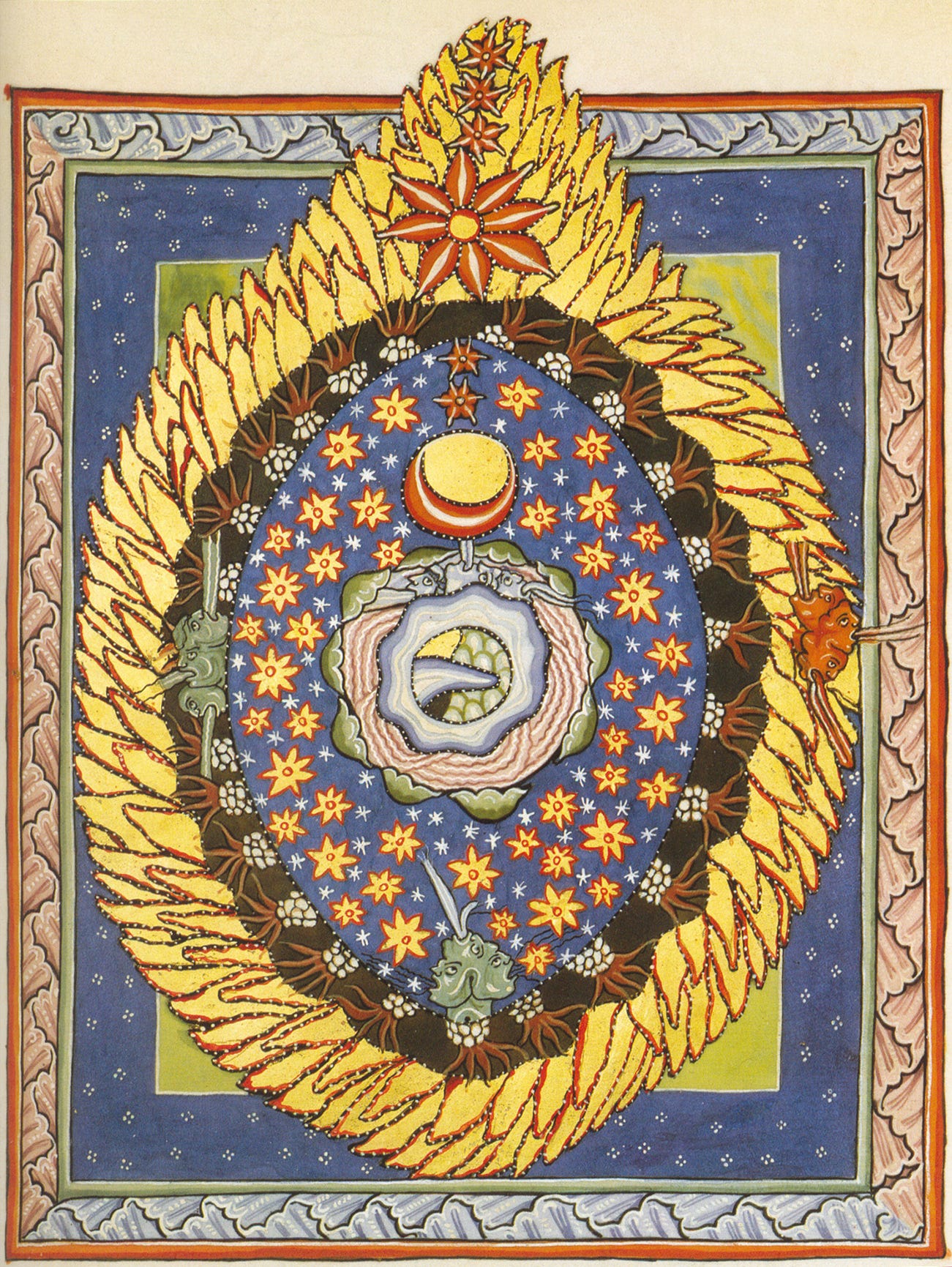

See Hildegard there with her man Volmar, scribing down her thoughts for her. The flames are a classical symbol for divine revelation, which perhaps explains how fiery these images can be.

Many visions Hildegard had were related directly to cosmology. What was a visionary? Well, someone who receives genuine visions from Jesus and/or Mary, usually for an important reason. Around Hildegard’s day and long after, there was a big issue with visionaries both because they were powerful and often radical in their ideas, but also because there was some worry over who exactly was inducing visions—demons, angels, or God/Mary. Such is the very fascinating literature on the “discernment of spirits”, which were basically ways to test a visionary’s legitimacy.

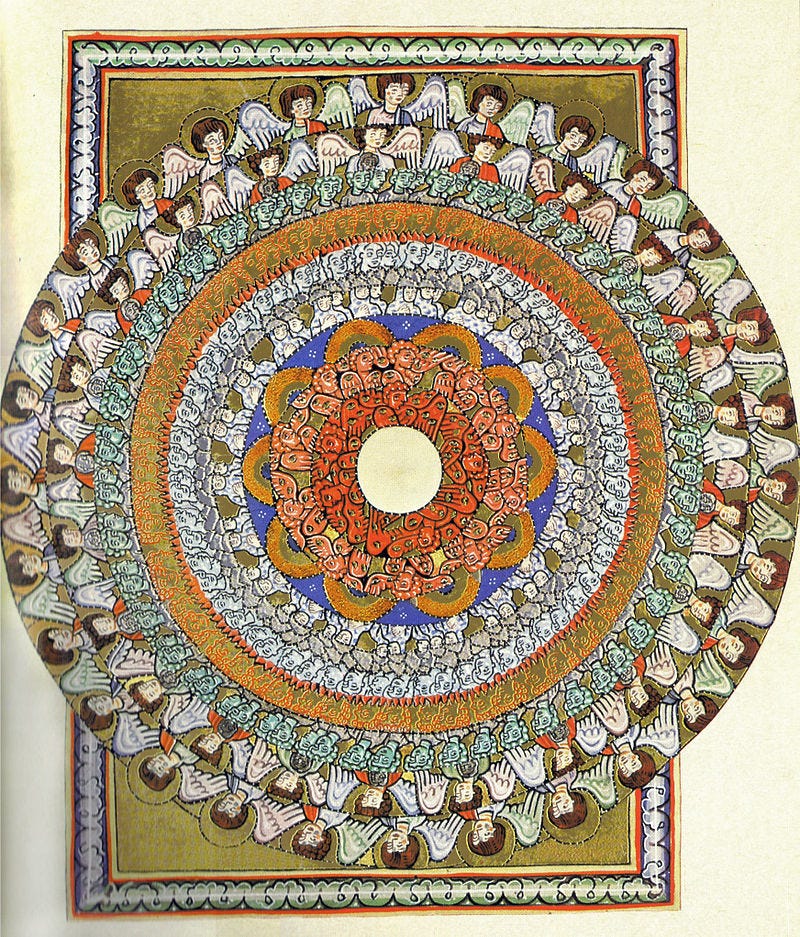

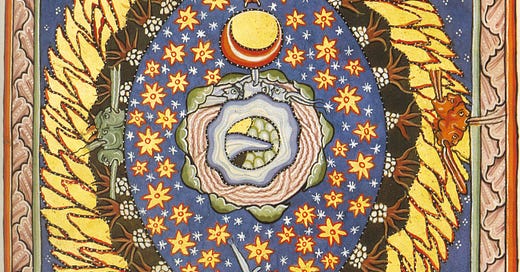

That aside, check out the manuscript illuminations made from Hildegard’s cosmological visions:

Notice the flames, and the faces. These are likely angels. Notice also the vulvic shape. Vulvas as an image in medieval devotional art are fascinating because they obviously relate to the source for mundane human life (birth) and God (Mary). My fav vulva digression is Christ’s wounds, which—due to a sword’s shape leaving vulvic holes—really emphasised this symbolism and imagery.

Sadly, the fantastical designs are really just that. The substance Hildegard gives us in her writings are no more or less explanatory than those found in the Bible. They complement Biblical cosmology well, but they don’t purport to define and explain it, the way the scholastic models did.

Hildegard’s cosmogony (creation) features in this short piece, so do follow up with her there:

Nicole Oresme

Oresme was a very deep thinker, fully immersed in the scholastic world—quite different from our previous entries. Oresme was very interested in mathematics and astronomy and could well work his own article. A few decades after he was theorising, we would have thinkers like Pierre d’Ailly, Copernicus, Bruno, Galileo, Tycho, and so on changing the model forever.

I’ve included Oresme because he wrangled with the problem of infinity. The scholastic model implied—if not directly posited—that the cosmology was limited, finite, ordered, and bound. This is in some ways accurate to God, but in others, it is against his omnipotent nature: why would God limit himself? I see Oresme coming in here, because he (tentatively, it must be said) theorised that there was either infinite universes or an infinite space in and beyond the Heavenly spheres. It would not be until Pascal many centuries later that such a claim was codified by a serious intellectual figure.

Since Oresme was very sophisticated and quite jargony in his ideas, I just want to drill down to the key concept I’m using him to embody—what was beyond the final sphere in the cosmos? For Oresme this was where a void, or in Historian of Science Edward Grant’s words, an extracosmic vacuum was thought to exist.

This is interesting because it had a theological dimension too—could God create the absence of things? Aristotle posited vacuums cannot exist in nature (‘nature abhors a vacuum’)—which is poignant because nature had a moralistic and anthropomorphic role in the medieval cosmos.

However, religious doctrine did not limit God’s power. Oresme thus married omnipotence and the vacuum, which by itself had interested medieval scholars for generations, under one (idiosyncratic) idea.

Besides Oresme there were few medieval philosophers who assumed the existence of an infinite void space beyond the world. These include the Jewish philosopher Hasdai Crescas (c. 1340–1410/11), Englishman Thomas Bradwardine (c. 1290–1349), Robert Holkot (d. 1349), and William Crathorn (fl. 1330s). But Oresme’s description is the most sophisticated from his immediate peers.

Oresme was concerned with the immensity beyond the Heavens, which he implies is God himself—in other words, only God is the extracosmic void (and he is everything else; but nothing else but God is the void).

Oresme is characteristic in positing this and I think there is something quite poetic about placing God directly with the very thing that Aristotelian orthodoxy seemed to argue was inherently anti-creation: the vacuum.

Thanks for reading.

Question:

There is an argument used by scholars and laypeople alike that Biblical (scholastic) cosmology is more somehow “safer” or more assuring—even comforting—especially because it is limited and lacks the mind-boggling, cosmically-horrifying infinity we now know. Do you agree with this view? Would you feel more secure if the universe was a discrete, divine, galactic onion?

Drop your thoughts below—I’d love to hear them, and any ideas for future posts you’d like to see.

If you liked this post and want more, why not check out:

I post at least once a week. Don’t miss out!

Subscribe to join me on this journey through medieval marvels and mysteries.

Maimonides argued that a great deal of the Bible including the garden of eden was metaphor so there is still wiggle room. He was primarily concerned with proving that God is not a physical being and painstakingly discussed sll the ways God is depicted as being physical as metaphor

https://open.substack.com/pub/scottkahn/p/itamar-ben-gvir-and-the-shame-of?utm_source=share&utm_medium=android&r=sllf3